Spending the most, living the least

The United States spends far more on health care than other large, wealthy countries. In 2023 the U.S. spent $13,432 per person. The peer-country average was $7,393. Health care also took 16.7% of U.S. GDP that year, well above peers. Yet U.S. life expectancy was 78.4 years in 2023, compared with 82.5 across the same peer group. That is a gap of 4.1 years, and every U.S. state sits below the peer average.

Why the gap? KFF’s breakdown points to higher deaths from overdoses and suicide and a heavier burden of chronic disease compared to peers. Those are solvable problems, but they sit outside the hospital as much as inside it.

Source: Health System Tracker

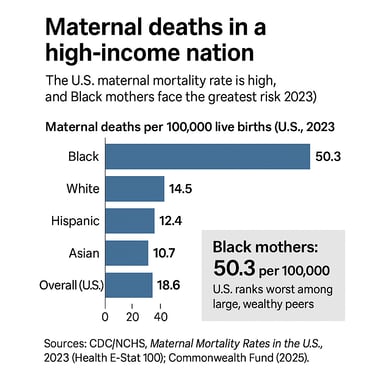

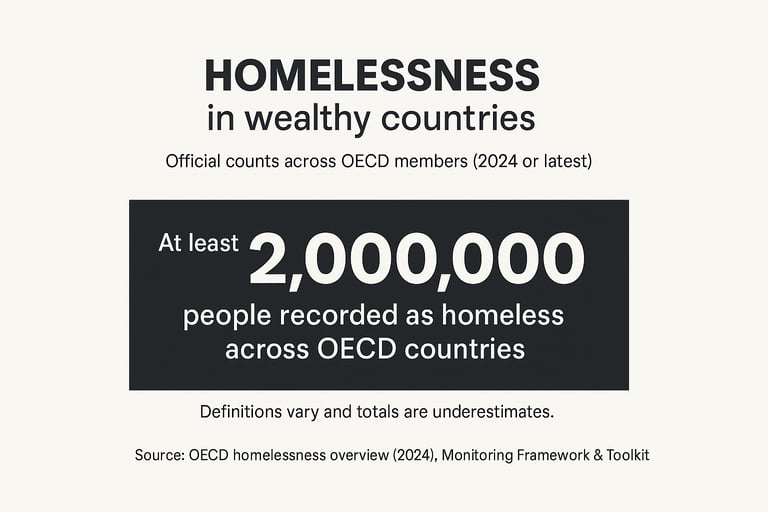

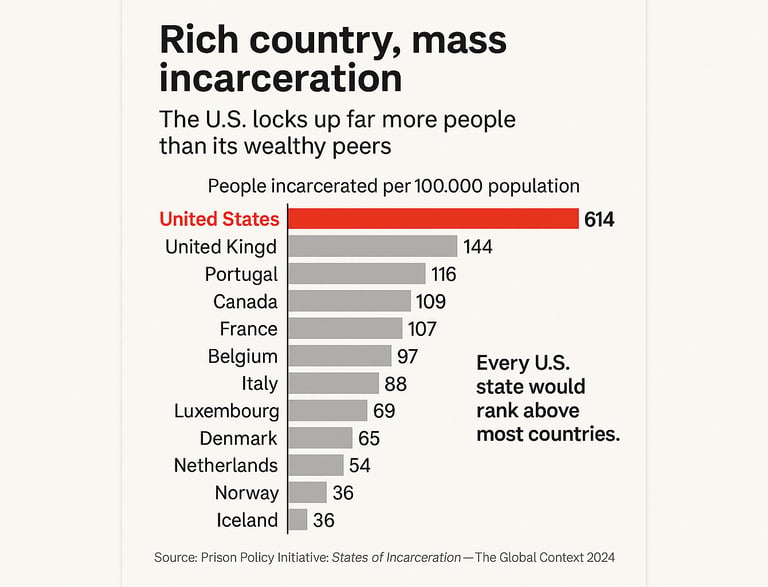

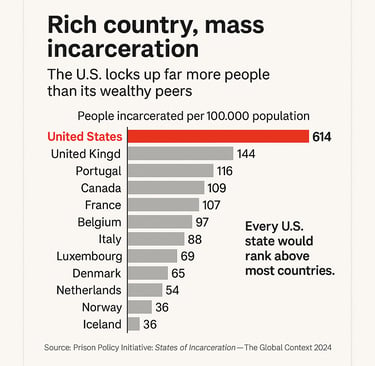

The prosperity paradox

Rich countries should be the easiest places to live long, safe, stable lives. Often they are. But on several basic measures, some of the richest nations deliver worse results than places with far less money. The pattern shows up in life expectancy, maternal deaths, incarceration, child poverty, and even homelessness. It isn’t about scarcity. It is about choices, systems,

and who benefits.

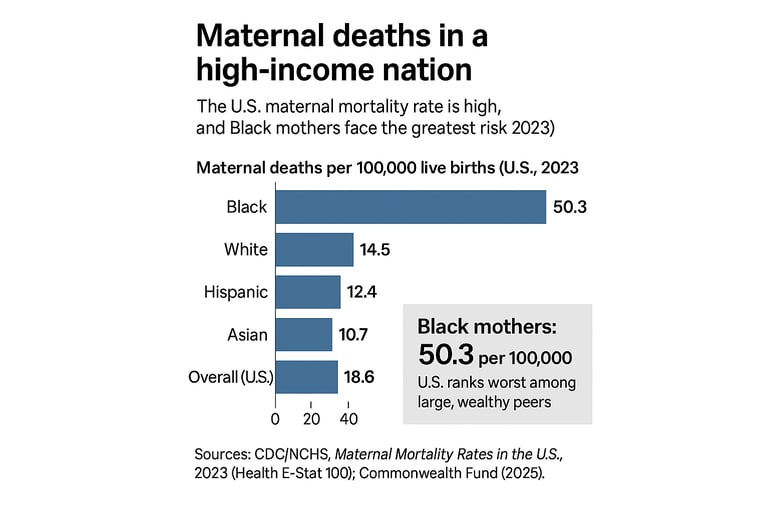

Maternal death in a high-income nation

Most wealthy countries have brought maternal deaths very low. The U.S. has not. In 2023, the national maternal mortality rate was 18.6 deaths per 100,000 live births. The risk is not shared equally. Black women faced 50.3 deaths per 100,000. Rates for White, Hispanic, and Asian women were 14.5, 12.4, and 10.7. These are official figures from the national vital statistics system. CDC

Comparative reviews put the U.S. well above other high-income countries, even after a post-pandemic dip. That is a rich-world outlier driven by access, quality, and social risks that follow women into pregnancy. Commonwealth Fund